The Makings of a Japanese Garden

|

One of the beautiful features about Japan is certainly the gardens. Japanese gardens tend to be minimalistic, and incorporate elements such as trees, rocks and sand to mimic natural scenery in an artistic manner. There are the famous “Three Great Gardens” in Japan, namely Kairakuen Garden in Ibaraki Prefecture, Kenrokuen in Ishikawa Prefecture, and Korakuen Garden in Okayama Prefecture. However, it should be noted that all these three gardens were created by feudal lords during the Edo period, when the so-called strolling gardens were popular. There are in fact, many other different styles of Japanese gardens. Let us take a look at how Japanese gardens has evolved through time.

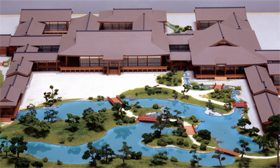

The earliest known gardens in Japan can be traced back to the Asuka and Nara periods. The strong influence of Buddhism and Taoism could be seen in the gardens of the imperial family and aristocrats. Additionally, there were attempts to recreate famous landscapes, with large ponds dotted with islands and sandy beaches to mimic the ocean landscape. Though unfortunately none of these gardens was preserved until today, the East Palace Garden on the Nara Palace Site was restored based on archaeological findings and opened to visitors in the 1990s. When the capital of Japan was shifted to Kyoto in the Heian period, aristocrats began to build gardens in the shinden-zukuri style. These stunning gardens were used for parties and recreational activities such as boating and fishing. Naturally, this means that this style of garden had large ponds, as well as bridges connecting islands that boats could pass under. Water features were a prominent presence also because Kyoto gets hot and humid in the summertime, thus the ponds and waterfalls helped people feel cooler. Again, none of these gardens was preserved until today. Towards the later Heian period, the concept of jodo (pure land) spread, and so did jodo gardens. These gardens resembled the image of Buddhist paradise as described in religious texts, typically featuring a large pond with lotus flowers, islands, Buddhist pavilion, as well as a bridge reaching the central island. Both the Motsuji Temple Garden in Iwate Prefecture and the Shiramizu Amidado in Fukushima Prefecture possess key characteristics of a jodo garden. In the Kamakura period, the power was shifted from the aristocrats to the warrior class. The latter embraced the Buddhist Zen sect, and this in turn influenced the style of Japanese gardens. Rather than build gardens to hold lavish parties and recreational activities, the gardens were built to assist monks in meditation and pursue religious advancements. In the subsequent Muromachi period, this style further developed and eventually gave birth to the karesansui style, otherwise known better as Japanese dry landscape gardens. The famous Ryoanji in Kyoto Prefecture has one, where rocks and sand are used to represent different landscape elements. We see the rise of tea gardens in the following Azuchi-Momoyama period, alongside the refinement of tea culture by Sen no Rikyu. Retaining a rustic and simplistic style that is reminiscent of the wabi spirit, tea gardens leaned towards a natural look and often included elements like stepping stones, stone lanterns and washbasins for ritual cleaning. Following this was the Edo period, and as mentioned, the strolling gardens or kaiyu style gardens grew popular, taking a step away from the previous minimalistic styles. The concept behind it was to enjoy different sceneries from different viewpoints each season, as one strolls through the large garden. These gardens usually incorporate ponds, rocks, trees, artificial islands and hills. On the flipside, tsuboniwa or courtyard gardens also became widespread. These gardens beautified the small space between buildings, and remain popular today. Western influences swept across as the Meiji period rolled in, giving rise to gardens with wide lawns. A good example is the Shinjuku Gyoen National Garden. Since then, Japanese gardens have continued to evolve, creatively integrating modern features with traditional Japanese elements, such as the Adachi Art Museum in Shimane Prefecture. No matter which style it is, Japanese gardens remain a source of beauty and tranquillity for everyone. |

Kenrokuen © Web Japan  East Palace Garden on the Nara Palace Site © Web Japan  Model of Higashi Sanjoden in ancient Kyoto © Web Japan  Shiramizu Amidado © Web Japan  Ryoanji © Web Japan  Tea pavilion at Sento Imperial Palace © Web Japan  Korakuen Garden © Okayama Prefectural Tourism Federation  Shinjuku Gyoen National Garden © Kurihara Osamu Federation |

Resources

|

“Japanese Gardens – Changes in Style”. 2019. niponica. https://web-japan.org/niponica/niponica26/en/feature/feature02.html. “Visit the “Three Great Gardens of Japan” to Enjoy a Stroll, Get Close to Nature, and Relax as You Look at the Scenery”. 2020. Web Japan. https://web-japan.org/trends/11_food/jfd202003_three-major-gardens.html. “Types of Gardens”. 2022. japan-guide.com Accessed 15 August. https://www.japan-guide.com/e/e2099_types.html . |

|

Japan Creative Centre 4 Nassim Road, Singapore 258372 +65 6737 0434 / jcc@sn.mofa.go.jp https://www.sg.emb-japan.go.jp/JCC/ Nearest parking at Orchard Hotel & Delphi Orchard |

|