Keeping Time with Omi Shrine

|

Shiga Prefecture is known for its lush nature: the prefecture itself encircles the largest freshwater lake in Japan, Lake Biwa, and 37% of its land area is designated to be protected as part of Natural Parks, the highest of any prefecture. However, it is also known for its splendid buildings, such as the historical Hikone Castle and the revered Omi Shrine.

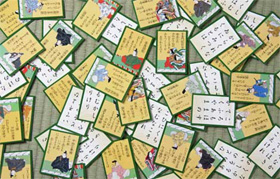

Unlike many of the other large and well-known shrines across the country, the Omi Shrine is actually a relatively new building. Plans to build it were first proposed in 1908, and the actual construction of it began only in 1937. The shrine itself is dedicated to Emperor Tenji, who reigned over Japan from 661 to 672. Every part of the shrine is a sight to behold, from its bright red torii gate and buildings, especially its main building, which is built in an architectural style unique to the region and registered as a Tangible Cultural Asset of Japan. Most notably, the shrine is decorated with many water clocks, or rokoku (漏刻) as they are known in Japanese. Emperor Tenji is said to have installed the first water clock in Japan, thus pioneering the tradition of official timekeeping in court. As such, the shrine has maintained a close connection with this time-telling invention. Every year in June, clock manufacturers bring their new products to the shrine as offerings, as part of a Water Clock Festival. The shrine also houses the Clock Museum and Treasure House. Established in 1963, it is the first clock museum in Japan. It houses paraphernalia related to timekeeping, such as water clocks, sundials, watches and other timepieces. Those interested in the history of timekeeping may be more interested in their collection of rare and ancient clocks, including those used in Japan, like lantern clocks and pendulum clocks (which were used not to tell time of day, but by astronomers to observe the skies). The museum also displays many of the shrine’s treasures, many of which are listed as Important National Cultural Property. But Omi Shrine is not only a sacred place for prayer: it is also considered a sacred place in the world of karuta. After all, the shrine is dedicated to Emperor Tenji, who composed the first poem in the famed Hyakunin Isshu anthology of Japanese poetry. His poem reads as follows: 秋の田の / aki no ta no かりほの庵の / kariho no io no 苫のあらみ / toma no arami わが衣手は / waga koromo de wa 露にふりつつ / tsuyu ni furitsutsu In the autumn fields the hut, the temporary hut, its thatch is rough and so the sleeves of my robe are dampened night by night with dew (Note: English translation by Joshua S. Mostow) Emperor Tenji’s poem, along with 99 others in the anthology, decorate the cards used in uta-garuta. The poems are split across two sets of cards: the yomifuda (読み札 ‘reading card’) and the torifuda (取り札 ‘grabbing card’). A designated reader will read a card from the deck of reading cards, and the players (who are paired up) will have to race to find the matching card from the set of grabbing cards before their partner does. |

© Raina Ong  © Biwako Visitors Bureau  © Omi Shrine  © AFLO  © Jiji |

|

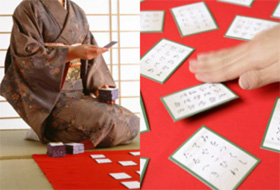

While uta-garuta can be played casually, it is also played competitively. In fact, competitive karuta (known as kyogi karuta ‘競技カルタ’ in Japanese) is widely recognised as a sport in the country. Players have to be alert in order to respond to the poem being read out, and then quickly and dexterously execute an arm swing that will get them the card they are aiming for. Listening and responding with grace and strength – this is not unlike what a sprinter might do in a race. Competitive karuta is known by many as “martial arts on the mat.”

And where else is a better battleground between competitive karuta players than the sacred grounds of Omi Shrine? The Shrine hosts a national championship tournament every January, and a national championship for high school students in July. The Grand Champion of the men’s division in the January championships is awarded the title ‘Meijin’, and the Grand Champion of the women’s division is known as ‘Queen’. Players who manage to clinch the title seven times are known as Eternal Masters. Karuta and the Omi Shrine has grown in popularity in recent years thanks to the manga series Chihayafuru. The series, which spawned an animated series and live action films starring an ensemble cast, shone a spotlight on the previously niche field of competitive karuta. Many young players have cited Chihayafuru as an inspiration for them to pick up the sport! The series has also helped spread information about competitive karuta, and traditional karuta in general, across the world; the pool of players grows every year to include more players from overseas! Though timekeeping and competitive karuta seem like two different worlds, they are connected through the enduring legacy of Emperor Tenji. If you are ever in Shiga Prefecture, do take the time to browse the grounds of Omi Shrine and its extensive collection of timepieces, and perhaps indulge in a speedy game of competitive karuta! |

© AFLO  © Yomiuri Shimbun  © Yuki Suetsugu/Kodansha Ltd. |

Resources

|

A Brief History of Japanese Timekeeping. (2016). Retrieved 30 August 2021, from https://allabout-japan.com/en/article/4498/ |

|

Japan Creative Centre 4 Nassim Road, Singapore 258372 +65 6737 0434 / jcc@sn.mofa.go.jp https://www.sg.emb-japan.go.jp/JCC/ Nearest parking at Orchard Hotel & Delphi Orchard |

|