The Resurgence of City Pop

|

Every era has trending music styles, some of which we can consider niche or timeless. The same can be said for Japan too. In particular, a Japanese music genre from the mid-1970s known as city pop, has recently garnered attention from across the globe, inducing a fond nostalgia in many listeners. What exactly is city pop and how did it rise in popularity again?

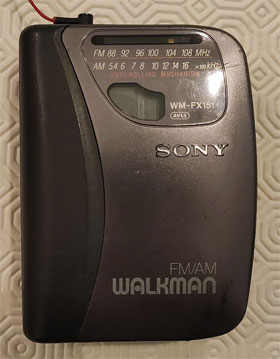

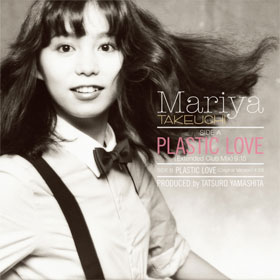

There is no unified or clear musical definition of city pop, as it was influenced by a diverse range of American music styles such as rock, pop, jazz, R&B, and disco. Generally, city pop broadly refers to pop songs with a “big-city feel”. Its western-style melodies and optimistic, carefree attitude defined itself from existing Japanese popular music styles, and gradually became popular among youths. Artists such as Yamashita Tatsuro, Takeuchi Mariya, Kadomatsu Toshiki and Arai Yumi are often associated with city pop. The rise of city pop corresponded with the development of Japan’s economy in the 1970s and 1980s, and the young generation leading more affluent lifestyles. It was common to see money spent on branded clothes, imported liquor, and international travel. At the same time, the economic boom and invention of related technologies further spurred music production and consumption. For example, cassette decks and FM stereos were incorporated into cars. The very first Walkman portable tape player was also invented during this period. All of these contributed to city pop becoming mainstream. Eventually, the bubble burst and economy slowdown happened in the early 1990s. The drastic change affected the trend of city pop. Additionally, other forms of music were gaining traction, and idols like SMAP, Kinki Kids and Amuro Namie would soon dominate the Japanese music industry and play a significant role to the J-pop wave abroad. City pop came into the picture again in the early 2000s when Japanese crate diggers starting playing mixes of Japanese vintage music from the 1970s and 1980s. International DJs and artists were also beginning to refer to city pop. The emergence of vaporwave and future funk on the Internet in the late 2000s, which sampled from city pop, was yet another factor. The ultimate push would come with the help of YouTube’s algorithm in the late 2010s. The most prominent incident was a 2016 future funk remix of Takeuchi Mariya’s “Plastic Love” by South Korean DJ and artist, Night Tempo. It was shared around so much that it surpassed the original song on search engines back then. The original song was not popular when it was first released in 1984. But it is now considered a city pop anthem, and Takeuchi Mariya even expressed her gratitude to Night Tempo. It was not clear what prompted YouTube’s algorithm to recommend that specific song. Nonetheless, it opened the gateway for international listeners to discover the wide discography of city pop. Another significant incident was Matsubara Miki’s “Mayonaka no door (Stay with me)”. An Indonesian singer, Rainych, covered it on YouTube, and it went viral. The original song also spread on TikTok, where users would play the song to their Japanese mothers to test their familiarity with the nostalgic song from 1979. The song was rereleased in 2021, and it reached number one on the global viral chart for 18 consecutive days. Major artists like Harry Styles and BTS member RM are also attributing to city pop. It is fascinating how city pop has returned to the spotlight decades later, and this time on an international scale. Music streaming services like Spotify, YouTube Music and Apple Music, have made it easier for people to appreciate city pop, with many users creating their own city pop playlist to share. Do you have a list of favourite city pop songs too? |

© Web Japan in collaboration with FACE RECORDS MIYASHITA PARK  © Web Japan in collaboration with FACE RECORDS MIYASHITA PARK  © YoloBoscaiolo, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons  © Warner Music Japan  © Pony Canyon Inc. |

Resources

|

“City Pop is Spreading Around the World”. 2022. Web Japan. https://web-japan.org/trends/11_culture/pop202203_city-pop.html. Zhang, Cat. 2021. “The Endless Life Cycle of Japanese City Pop”. Pitchfork. https://pitchfork.com/features/article/the-endless-life-cycle-of-japanese-city-pop/. Arcand, Rob & Goldner, Sam. 2019. “The Guide to Getting Into City Pop, Tokyo’s Lush 80s Nightlife Soundtrack”. VICE. https://www.vice.com/en/article/mbzabv/city-pop-guide-history-interview. Salazar, Jeffrey. 2021. “Memory Vague: A History of City Pop”. University of Massachusetts Amherst. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/1092/. St. Michel, Patrick. 2022. “Phung Khanh Linh and artists abroad get creative with city pop palette”. The Japan Times. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2022/12/15/music/city-pop-abroad/. |

|

Japan Creative Centre 4 Nassim Road, Singapore 258372 +65 6737 0434 / jcc@sn.mofa.go.jp https://www.sg.emb-japan.go.jp/JCC/ Nearest parking at Orchard Hotel & Delphi Orchard |

|