Salt-making in the Noto Peninsula

|

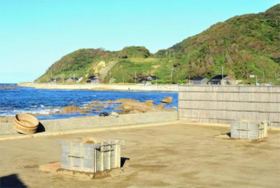

Jutting out from the mainland into the Sea of Japan, the Noto Peninsula cuts a lonely figure in the northern part of Ishikawa Prefecture. Although it is far from bustling cities and transport connections, it still draws many visitors eager to soak in its picturesque coastal scenery. The side of the peninsula that faces the rough seas of the Sea of Japan is laced with rugged terrain, while the inner coast faces inland and enjoys calmer waters. This idyllic inner coast is known as Okunoto (奥能登), and is closely associated with traditional salt-making.

Traditional salt-making in the Noto Peninsula can be traced back to the 5th century. Back then, small ceramic pots were used to boil seawater and obtain salt. However, this technique became obsolete and soon gave rise to the agehama technique by the 8th century. Seawater is drawn and spread on sand fields with a conical bucket. Workers rake the sand throughout the day to allow the water to evaporate, thereby producing crystallised salt. These crystals are collected and boiled down with more seawater in kilns to produce salt. This produces salt that is high in mineral content, giving it its distinct briney taste. Although it is hard work that takes years to master, this technique is the most ideal for Okunoto’s landscape and climate. From 1583 to 1869, Ishikawa Prefecture was part of the Kaga Domain. The heads of the domain had an immense influence on the infrastructure, food, and crafts of the region. Places like Kenrokuen Garden and Kanazawa Castle are all remnants of their legacy that can still be seen in Kanazawa City today. It was also thanks to them that salt-making has become so inextricably linked with the rural landscape of the Noto Peninsula. During the Edo Period, Japan’s currency and taxation system was based on rice. A portion of each domain’s rice crop yields had to be paid to its leaders as tax, and turned into currency. It is needless to say then that the more rice a domain could produce, the more wealthy a domain could become. The Kaga Domain’s yield of one million koku (one koku is equivalent to 180 liters) placed it firmly as the wealthiest domain in Japan at the time. Rice was the most common crop in the region, but on the Noto Peninsula, farmers instead relied on salt. In response to the lack of cultivable land available on the peninsula, the leaders of the Kaga Domain devised a ‘rice for salt’ system, under which farmers could pay their taxes in the form of salt. Salt-making became a large and respectable industry on the Noto Peninsula, producing so much salt that it soon held a monopoly on the country’s salt trade. |

© photoAC  © photoAC  © Ishikawa Prefecture  © pakutaso |

|

However, the end of the Edo Period marked the steady decline of the salt industry in the peninsula. New economic policies introduced by the new central government meant that the Kaga Domain no longer held a monopoly on salt, and salt farmers were leaving their fields and terraces to seek employment opportunities elsewhere. The modernisation of salt-making methods threatened the traditional salt-making further, and it was not until the 1990s that steps were taken to protect the cultural and historical value of agehama-style salt-making. Agehama-style salt-making was designated an intangible folk cultural asset of Ishikawa Prefecture in 1992 by the Agency for Cultural Affairs; later in 2008, it was designated a national intangible folk cultural asset. This recognition encouraged the revival of traditional salt-making techniques and also drew more tourists to the Noto Peninsula.

Salt harvested using the agehama method is said to have higher mineral content and a mild, natural flavour. Although Kaga-ryori (cuisine derived from the Kaga Domain) is known for its fresh seafood and wagyu, it would not be a stretch to say that the flavours of these delicacies have been brought out by the region’s salt. Besides being used as seasoning as is in dishes, it is also used to make shio koji (塩麹), a type of fermented rice malt. Shio koji is used to marinate meats and seafood; it makes flesh more tender and brings out more of the ingredient’s umami flavour. Agehama salt is also increasingly used in snacks like ice cream, cookies, and breads, which have drawn the attention of the younger populace. Tourists can still visit salt farms in Okunoto to not only see how salt is made traditionally, but to even try it for themselves! If you ever find yourself in Ishikawa Prefecture, why not make the trip up the peninsula to have a taste of agehama-style salt? |

© photoAC  © Ishikawa Prefecture  © photoAC |

Resources

|

Cocora, L., & Brand, K. (2010). Preserving Japan's Sea Salt Making Tradition. Retrieved 30 April 2021, from https://ourworld.unu.edu/en/preserving-japans-sea-salt-making-tradition |

|

Japan Creative Centre 4 Nassim Road, Singapore 258372 +65 6737 0434 / jcc@sn.mofa.go.jp https://www.sg.emb-japan.go.jp/JCC/ Nearest parking at Orchard Hotel & Delphi Orchard |

|