Through the Lens of Japan's Greatest Filmmakers

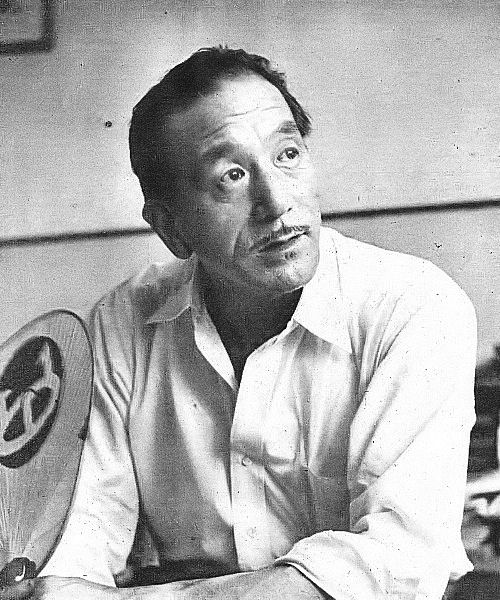

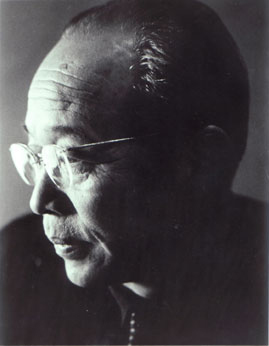

The 2021 Japanese film Drive My Car, directed by Ryusuke Hamaguchi, has recently made history by becoming the first Japanese film nominated for Best Picture at the upcoming Oscars. The film has also garnered nominations for Best Director, Best International Feature Film, and Best Adapted Screenplay. Aside from the Oscars, this Japanese production has also received recognition and accolades across the European film festival circuit. The film’s international acclaim has no doubt propelled Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s status in the Japanese film industry, closer to that of perennial icons like Yasujiro Ozu, Akira Kurosawa, and Kenji Mizoguchi. Although there are several other Japanese directors that have shaped the course of Japanese film history, it is often these three that are considered representatives of Japanese cinema’s golden age in the 1950s. They had visions and techniques that were groundbreaking, resulting in films that were able to transcend national borders and draw appreciation and reverence from audiences worldwide. Yasujiro Ozu was a prolific filmmaker who was active between 1929 and 1963, and whose works spanned several genres. However, he is most known for the “domestic dramas” that he made later in his life. Ozu was a trailblazer in the industry, developing a style that was simple, delicate, and extremely “Japanese”. Rather than flashy plot-driven action, Ozu focused on minimalistic storytelling: muted, restrained drama that centred on family life. To further evoke the audience’s emotion, Ozu placed his cameras close to the ground and stationary, and shot dialogue head-on. This created an effect of a mismatched eyeline. Audiences were forced to look slightly up at the speaker, rather than at eye level or above as though transcendent, or an outside. Characters would speak about events, but Ozu would omit them from the film. His techniques both disoriented the audience, and brought them closer to the heart of the story, making them feel like they have been immersed in an intimate conversation with family. He was also fond of using transitional ‘pillow shots’. This refers to cutaway shots of seemingly unrelated scenery or objects such as teapots or laundry. Perhaps the most famous of Ozu’s films is 1953’s Tokyo Story. It is widely regarded as Ozu’s magnum opus, and is often referred to as a masterpiece and one of the greatest films ever made. Other stand-out films include Late Spring (1949) and Early Summer (1951) which, together with Tokyo Story, complete Ozu’s famous Noriko Trilogy, which all feature long-time collaborator Setsuko Hara starring as a woman named Noriko. A more light-hearted watch is Good Morning (1959), which follows two young boys who, desperate for their parents to buy them a television set, go on a strike on pleasantries. His style and legacy lives on in the work of contemporary Japanese filmmakers like Hirokazu Koreeda, who is also well-known for his earnest, minimalistic portrayals of family life in Japan. Where Ozu looked within, building on a characteristically Japanese style, Akira Kurosawa was a filmmaker that had an international outlook towards filmmaking. Kurosawa was active for a long time between 1936 and 1993, and many pinpoint his style as a bridge between Western and Eastern filmmaking ideologies. He was heavily influenced by Western playwrights and authors, and was also very receptive of narrative styles and filming techniques that were more common in Hollywood. He most famously adapted Shakespeare’s play King Lear into a samurai film, Ran (1985). The core message of the story, the ambitions and violent personalities of the characters remained the same, but instead of the royal courts of England, he inserted the political intrigue and tragedy into the world of samurai. By doing so, he made Western source material more relatable to Japanese audiences and at the same time, made contemporary Japanese cinema more accessible to audiences outside the country. Kurosawa’s films were like parables; they provided scathing critiques on society, while still entertaining audiences with dramatic action and riotous comedy. Though he is said to have made several masterpieces over the course of his career, he is most known for epic, action-packed samurai films such as Seven Samurai (1954) and Yojimbo (1961), and gritty dramas like Stray Dog (1949), which was one of Japan’s earliest detective films and a precursor to the ‘buddy cop’ genre! 1950’s Rashomon is also another one of Kurosawa’s most seminal pieces of work and often considered one of the greatest films ever made. It was also the first Japanese film to win an international award: the Golden Lion at the 1951 Venice Film Festival. Receiving this honour gave Kurosawa international recognition, and introduced many Western audiences to the wonders of Japanese cinema. Contemporary American filmmakers George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, and Martin Scorsese have all named Kurosawa as major influences on their own filmmaking careers. Though he started his career many years before Ozu and Kurosawa, Kenji Mizoguchi may be name that is less recognisable to non-Japanese film lovers. Like Ozu, Mizoguchi favoured a more minimalistic, and refined aesthetic in his films. However, where their styles diverge is in the way Mizoguchi choreographed his shots. Mizoguchi was greatly influenced by Japanese theatre, and often incorporated styles of various Japanese theatrical forms into his work. He was a fan of long, sweeping takes, of travelling shots that built up the emotional tension of the scene. He was a painter in his youth, and that training often came through in the elegant composition of his frames. Underneath the beautiful surface of his shots lies turbulent emotion. Indeed, Mizoguchi was critical of contemporary society, and was not shy about the subjects he wanted to portray in his films, such as social injustices, oppression, and the unfair position of women under patriarchy. This interest is evident in films like Women of the Night (1948), a gritty contemporary film (as opposed to his usual oeuvre of historical dramas) that followed a group of women weathering the hardships of post-war Japan. It can also be seen in his historical films, such as The Life of Oharu (1952), a powerful and heart-breaking adaptation of a 17th-century novel that followed the spiralling downfall of the daughter of an imperial court samurai; and Sansho Dayu (1954), which tells the emotional and tragic tale of a family torn apart. Ugetsu (1953) is a supernatural romance film that delves into a relationship between a person and a spirit, and explores themes of the impacts of patriarchy. It is oft considered one of the most definitive works to be released during the golden age of Japanese cinema. This film, together with Kurosawa’s Rashomon, helped to generate more buzz and awareness of Japanese films and filmmakers. The Japanese film industry is always growing, with brilliant filmmakers constantly pushing the envelope with innovative and creative techniques and ideas. While waiting for the next instalment of the Japanese Film Festival in Singapore, why not take a retrospective trip through time by watching the works of the Japanese directors we have introduced here in this article? |

|

Resources

|

"A Film Legend: Events Worldwide Memorialize Film Director Yasujiro Ozu". 2003. Web Japan. https://web-japan.org/trends01/article/030228fas_r.html. "A Japanese Director’s Lasting Influence On American Cinema". 2017. American View: U.S. Embassy Japan Official Magazine. https://amview.japan.usembassy.gov/en/japanese-directors-lasting-influence-on-american-cinema/. Brody, Richard. 2014. "Better Than Ozu And Kurosawa: Mizoguchi". The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/better-than-ozu-and-kurosawa-mizoguchi. Charpentier, Dave. 2021. "West By East By West: The Influence Of Akira Kurosawa On The West And Vice Versa, Popmatters". Popmatters. https://www.popmatters.com/akira-kurosawa-international-filmmaker. Holland, Norman. 2022. "Ozu's Style In Late Spring, Early Summer, And Tokyo Story". Asharperfocus.Com. Accessed February 24. https://www.asharperfocus.com/Ozu-style.html. Schilling, Mark. 2020. "Shochiku Celebrates A Century Of Japanese Cinema Hits". The Japan Times. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2020/04/10/films/celebrating-century-cinema-hits/. Sharp, Jasper. 2020. "Kenji Mizoguchi: 10 Essential Films". British Film Institute. https://www2.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/news-bfi/lists/kenji-mizoguchi-10-essential-films. Sharp, Jasper. 2019. "Yasujiro Ozu: 10 Essential Films". British Film Institute. https://www.bfi.org.uk/lists/yasujiro-ozu-10-essential-films. Westby, Alan. 2020. "Films From The Golden Age Of Japanese Cinema". Los Angeles Public Library. https://www.lapl.org/collections-resources/blogs/lapl/films-golden-age-japanese-cinema. |

|

Japan Creative Centre 4 Nassim Road, Singapore 258372 +65 6737 0434 / jcc@sn.mofa.go.jp https://www.sg.emb-japan.go.jp/JCC/ Nearest parking at Orchard Hotel & Delphi Orchard |

|