Ryokan: A Place to Relax and Refresh Oneself

|

If you have visited Japan, you may have chosen to stay at a ryokan (Japanese traditional inn) before. Unlike hotels, staying the night at a ryokan provides an entirely different experience. The moment you step past the entrance, you remove your shoes and check in. You are then led to your room, which typically has tatami (straw mat) flooring and sliding shoji (paper screen) doors. There is also a tokonoma (small alcove), where a simple flower arrangement and painting or calligraphy may be on display. You may sit on a zabuton (floor cushion) next to a low table, and be served Japanese tea and snacks. There are no beds in the room, and instead futon (traditional mattress) and bedding will be laid out on the floor for you. You can also change into yukata (casual Japanese robe) and wear it freely around the ryokan.

There is no need to worry about your meals too. Staff called nakai will see that you are promptly served. The okami (landlady) may also make her rounds to check on you and see that your needs are met. Apparently, the essence of their service can be described as age-zen sue-zen: serving delicious meals and clearing the dinnerware without guests having to say anything or trouble themselves. Indeed, the keywords of a ryokan stay are the guest’s comfort and relaxation. In addition, one of the appeals of staying at a ryokan is certainly enjoying the bath. After all, soaking in hot water is a perfect way to wind down and relax. It is common for guests to take a dip several times, such as during the night and another the next morning. In fact, short trips to hot springs known as toji (hot spring therapy) were common during the Edo period. Slowly, travellers started to stay overnight for both the cure and the enjoyment. The term ‘ichi-ya toji’ was coined as a result, with ichi-ya meaning “one night”. Hence, this developed into the custom of staying one night and part of two days. In which case you may wonder: How did the concept of ryokan come about? Let us first look at the Nara period. During this period, transportation and traffic networks were not as developed. As such, travelling in Japan had its risks and dangers, especially if people had to sleep outdoors. A number of travellers even died of starvation, prompting Buddhist monks to take action. This led to fuseya (free rest houses) being built for travellers in Japan to stay overnight. In the Kamakura period, there were also kichin-yado (cheap inn). It was named so because no meals were provided. Instead, travellers were charged for the wood used in cooking their own meal. Moving forward to the Edo period, Japan’s political situation stabilised with the Tokugawa shogunate (military government) in reign. Highways were constructed and the economy grew, leading to frequent trips by merchants. In order to accommodate these merchants, hatago (traveller’s inn) which provided meals were built. While kichin-yado and hatago co-existed for a while, hatago eventually became the mainstream by the latter half of Edo period. At the same time, the shogunate established the sankinkotai system, where daimyo (feudal lords) were obliged to reside in Edo or their domains alternatively. This system aimed to prevent daimyo from gaining too much power, forcing them to pledge allegiance to the shogunate. Thus, when they had to travel to Edo and back, the entourage would stay at honjin (troop headquarters) that were located in shukubamachi (post towns) along the highways. As the years went by, these places declined and some even became historic sites. However, the appeal and hospitability provided by these places continued on in Japanese culture. One can say that hatago and honjin are the direct precursors to ryokan. Interestingly, the oldest hotel in the world certified by the Guinness World Records is actually a ryokan in Japan. Koshu Nishiyama Hot Spring, Keiunkan, which is located in Yamanashi prefecture, was founded in 705AD by Mahito Fujiwara and has a history of over 1,300 years. The family’s descendants have continued to operate the ryokan for 52 generations until today. Numerous significant figures have stayed there, including feudal lords Ieyasu Tokugawa and Shingen Takeda. It was even known as their secret hot spring. So the next time you visit Japan, instead of a hotel, why not stay the night at a ryokan to refresh yourself? |

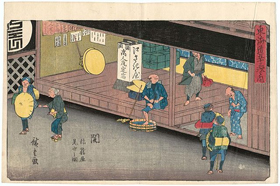

© Kawabe Akinobu  © Sugawara Chiyoshi  © Kono Toshihiko  © Web Japan  Seki: The Inn (Seki, Hatagoya mise no zu) (© Hiroshige Utagawa, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)  Seki: Early Departure of a Daimyō (Seki, honjin hayadachi) (© Hiroshige Utagawa, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)  Koshu Nishiyama Hot Spring, Keiunkan (© Boltor, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons) |

Resources

|

“Stay in a Ryokan and Savor an Atmosphere Like a Japanese Home”. 2015. niponica. https://web-japan.org/niponica/niponica16/en/feature/feature02.html. “Ryokan in Tokyo – A Unique Japanese Experience in the Capital of Japan”. 2017. Web Japan. Accessed 17 May. https://web-japan.org/trends/11_food/jfd170817.html. Sanada, Kuniko. 2006. “Traditional Hospitality in Japan”. NIPPONIA. https://web-japan.org/nipponia/nipponia39/en/feature/feature02.html. Yamaguchi, Yumi. 2003. “Staying the Night at a Spa”. NIPPONIA. https://web-japan.org/nipponia/nipponia26/en/feature/feature01.html. “Origins and History of the Japanese Ryokan”. 2010. Japan Ryokan & Hotel Association. Accessed 17 May. https://www.ryokan.or.jp/past/english/pdf/origins_and_history.pdf. “Koshu Nishiyama Hot Spring | Keiunkan ”. 2022. Keiunkan. Accessed 17 May. https://www.keiunkan.co.jp/en/. |

|

Japan Creative Centre 4 Nassim Road, Singapore 258372 +65 6737 0434 / jcc@sn.mofa.go.jp https://www.sg.emb-japan.go.jp/JCC/ Nearest parking at Orchard Hotel & Delphi Orchard |

|