Colourful Summer Nights: Fireworks in Japan

|

Summer days in Japan are hot and humid; the heat from the sun beats down relentlessly, bringing the temperatures close to 35ºC at its peak. When night falls, however, the summer skies are often filled with the iridescent colours and lively sounds of fireworks. Fireworks festivals, known as hanabi taikai (花火大会) in Japanese, are a staple of Japanese summers, and are held all over Japan during the season.

It is claimed that fireworks were first introduced to Japan in the 1600s through trade with foreign traders. However, it was not until the 1700s that fireworks as a summertime tradition was popularised. In 1733, after a pandemic swept through Edo, a local Buddhist temple decided to organise a remembrance service for those who had lost their lives by setting lit candles afloat on the Sumida River. Craftsmen were allowed by the then-shogun, Tokugawa Yoshimune, to use his stored military gunpowder to create fireworks display called the Ryogoku Kawarabiraki Fireworks Festival to placate the citizens that came to pay their respects to the dead. Only twenty fireworks were displayed then, but this event quickly set a precedent, and this festival quickly became an established summertime tradition. Year after year, the number of people who came to the Sumida River to admire the display grew, and so did the number of participating pyrotechnicians. Rivalries began to emerge between guilds of pyrotechnicians, with the Tamaya (玉屋) and Kagiya (鍵屋) guilds being the most prominent. The festival took on the atmosphere of a competition, with each guild trying their best to wow the crowd and out-do the other guilds with elaborate fireworks displays. |

© Web Japan  © Web Japan  © Nagaoka Hanabi / Nagaoka Festival Organizing Council |

|

Today, this historic festival is now known as the Sumidagawa Fireworks Festival, and is held every July on the last Saturday of the month. It is the biggest fireworks event in Tokyo, lasting for over 90 minutes, and attracting over a million admirers annually. Competitions for the best viewing spots are fierce, and crowds choke up parts of the city surrounding the river well before and after the festival has ended.

Japanese fireworks come in four general categories. The first, warimono, are known as the quintessential Japanese fireworks. Warimono explode outward in a spherical shape and subcategories such as the chrysanthemum-type warimono (circular firework with “stars” streaming out from its middle) and the peony-type warimono (circular firework with “stars” that stream less) are the most commonly seen. There are pokamono, which refer to fireworks that have “stars” streaming down or in random directions. Subcategories include the bee-type pokamono that has “stars” that spin around like agitated bees. Hanwarimono are fireworks that are half warimono and half pokamono. Small shells of warimono and pokamono fireworks are contained in a larger shell, which creates a spectacular show of fireworks going off all at once when they are released. Katamono may be the most modern of the four types, referring to fireworks that create specific shapes when they are released. Common shapes include hearts and smiley faces, although more complex shapes like animals and even anime characters have also become frequent sights at recent festivals. |

© Aflo  © Pakutaso |

|

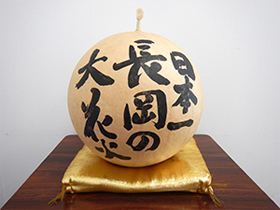

The Sumidagawa Fireworks Festival also serves as the blueprint for a variety of small and large-scale fireworks displays across Japan today. Some festivals take advantage of their location, such as the Okazaki Fireworks Festival (Aichi prefecture) and Suwako Matsuri Fireworks Festival (Nagano prefecture) where visitors can admire fireworks with beautiful scenery as a backdrop. There are also competitions where the country’s top pyrotechnicians gather to show off their creations, such as the Tsuchiura All Japan Fireworks Festival (Ibaraki prefecture) and the Omagari National Japan Fireworks Competition (Akita prefecture).

Although a damper has been put on this year’s festival circuit, many of Japan’s pyrotechnicians have come together to plan for a surprise display of fireworks all over Japan. This project, titled Cheer up Hanabi, aims to bring encouragement and highlights fireworks artisans’ hope for the end of the spread of COVID-19. The display can be viewed online and more information can be found on their website here: https://www.cheeruphanabi.com/pg2792762.html In person, these annual festivals are sure to be up and raring to go by next year! Why not make plans to view a fireworks festival if you are planning a summer holiday in Japan next year? |

© Web Japan  © Edogawa Fireworks Festival Execution Committee |

Resources

|

Deaver, L. (2020). Summer Sky: The Four Types of Japanese Fireworks. Retrieved 14 May 2020, from https://blog.gaijinpot.com/four-types-of-japanese-fireworks/ |

|

Japan Creative Centre 4 Nassim Road, Singapore 258372 +65 6737 0434 / jcc@sn.mofa.go.jp https://www.sg.emb-japan.go.jp/JCC/ Nearest parking at Orchard Hotel & Delphi Orchard |

|