Onigiri: Japan’s National Soul Food

|

One can say that onigiri (rice ball) is the soul food of Japan, with it being a staple of Japanese meals for a long time. It is portable, easy and quick to prepare, making it the ideal choice for a packed lunch when travelling out for a school excursion or a picnic. Aside from being a favourite menu in the home kitchen, onigiri is also a popular item in convenience stores, with shelves full of rice balls filled with different ingredients. There are even cafes specialising in onigiri.

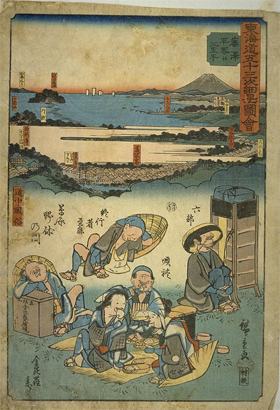

The triangular-shaped rice ball wrapped with dried seaweed can have a variety of fillings, such as umeboshi (Japanese pickled plum), grilled salmon or mentaiko (marinated cod roe). Some other variations include using different types of rice other than white rice, be it fried rice or rice with red beans. The rice ball can also be coated with miso or soy sauce, and then grilled for a crispy texture. Either way, it is a relatively healthier choice compared to many fast foods that are cooked with oil. The exact origins of onigiri are not clear. However, carbonised rice clumps were unearthed in late Yayoi Period ruins in the former Rokusei town of Ishikawa Prefecture, which indicate that onigiri has been around for at least 2,000 years. A stark difference is that the rice balls then seemed to be wrapped in bamboo leaves in a corn-like shape, and boiled or steamed. The “Roku” in “Rokusei” sounds similar to “six” in Japanese, and the 18th of every month is rice day as the kanji for ten (十) and eight (八) can be found in the kanji for rice (米). Hence, June 18 is known as Ongiri Day in Japan. It was only during the Heian Period that we see traces of the onigiri which we know today. Known as tonjiki (頓食), the rice balls were shaped like eggs and given to servants during events at imperial or noble households. Later during the Sengoku Period, the rice balls were carried as rations by troops. Even then, an umeboshi was commonly stuffed inside rice balls, as its antibacterial properties helped to keep the rice fresh. Initially, onigiri were wrapped in dried bamboo sheathes. The familiar custom of covering them with dried seaweed only became widespread during the Edo Period. At the same time, onigiri also became widespread among the common people, becoming the ideal portable food for travel and during cherry blossom or fireworks viewing. Depiction of this can be found in Hiroshige Utagawa’s “The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido” woodblock prints. Another significant change happened in the 1970s. Convenience stores developed the innovative packaging we know today, which kept the dried seaweed separate from the rice, thus keeping the seaweed fresh and crispy and allowing customers to wrap the rice without it sticking to their hands. Convenience stores also started selling non-traditional Japanese flavours like tuna and mayonnaise, due to overseas influence. These changes greatly contributed to the popularity of onigiri sold in convenience stores. Although majority of Japan refer to it as onigiri, it is also called omusubi in the Kanto-Tokaido regions with the exception of Tokyo and Kanagawa Prefectures. In any case, the name difference may boil down to the different dialects across Japan. Lately, onigirazu has been trending. Its shape is more like a sandwich, and is made by spreading rice on dried seaweed, and layering ingredients on top. The seaweed is folded across to form a square shape, and everything is cut into half like a sandwich. The steps are easy, and people are free to experiment with the ingredients. The cross-section of an onigirazu is also visually eye-catching, allowing people to come up with their own creative arrangements. Previously one of JCC’s staff also made her own version of onigirazu! While onigiri looks simple at first glance, upon examining it in detail, we discover why it has come to represent Japan as a national soul food. If you are craving for a quick and filling meal next time, how about making your own onigiri or the more recent onigirazu? |

© Web Japan  © PIXTA  Fujisawa: Pilgrims Resting, “The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido” (© Hiroshige Utagawa, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)  © Seven-Eleven Japan Co., Ltd.  © photoAC  © Aflo, amanaimages Inc. |

Resources

|

“GREAT BALLS OF RICE!”. 2003. Web Japan. https://web-japan.org/trends01/article/030121soc_r.html. “Japanese Soul Food”. 2017. niponica. https://web-japan.org/niponica/niponica20/en/feature/feature06.html. "【1月、6月】おにぎりの記念日ってありますか?". 2022. GOHAN SAISAI. Accessed 20 June. https://www.gohansaisai.com/know/entry/detail.html?i=224. Kurihara, Juju. 2015. “History of Onigiri”. IroMegane. http://www.iromegane.com/society/history-of-onigiri/. “Onigiri Rice Balls”. 2016. Kikkoman. https://www.kikkoman.com/en/foodforum/close-up-japan/30-3.html. “Onigiri (rice balls)”. 2022. EDOPON CO., LTD. Accessed 20 June. https://restaurants-guide.tokyo/column/onigiri-rice-balls/. |

|

Japan Creative Centre 4 Nassim Road, Singapore 258372 +65 6737 0434 / jcc@sn.mofa.go.jp https://www.sg.emb-japan.go.jp/JCC/ Nearest parking at Orchard Hotel & Delphi Orchard |

|